Also called Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate, Prince’s Feathers, Persicaria orientalis, Polygonum orientalis, Oriental Persicary, Ragged Sailor, Lady’s Fingers, and by many other names.

THE BASICS: HOW TO GROW KISS-ME-OVER-THE-GARDEN-GATE

Plant these seeds in a sunny spot in the ground or in a large container. Although Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate has grown in the United States for almost three hundred years, it is a non-native species, so do not plant near protected wetlands.

This plant has a tricky side and an easy side.

Here’s the tricky side: It needs to be stratified. What does that mean? The seeds need to experience winter to germinate successfully. If you live in a climate with a traditional winter, shallowly sow them outside in fall, winter, or very early in the spring. If the ground is already frozen, sow them under some leaves or beneath the snow level. If you live in an arid climate with warm winters, put your seeds in damp sand, peat moss, or paper towels in a labeled Ziploc bag in the fridge for at least two months, and then plant outside at the beginning of spring.

Here’s the easy side: Once germinated, the plants need very little care. Regular watering and fertilizer will help, but this species will grow even in neglected conditions. Each plant forms a single, strong stalk that, unlike a sunflower, does not need to be staked or supported. They will grow through the spring and summer, getting between 5-11 feet in height. In August, flowers will emerge and then slowly hang over in deep-pink bunches until frost kills them. These are annual plants (they live for one growing season and die), but they drop seeds that you can either collect or let grow the following year.

MY OWN EXPERIENCE

In spring 2019, I bought seeds from Seed Savers Exchange (not currently available, but I have links at the end) and immediately planted them outside. Unfortunately, none of them germinated. What a disappointment!

2020, I swore, would be different (I wasn’t wrong, there!).

In late winter I filled two containers (each about 2-3 gallons in size) with soil and planted several seeds in each about ¼” below the soil level. And then I waited, and waited, and waited.

It wasn’t until mid-April, around the last frost date for my region, that the seeds germinated. The cotyledons, the first simple leaves to sprout, are slender, delicate, and red, turning green as the stems thicken.

The true leaves that next form are large and bright green, emerging from a collar that continues to thicken and grow as they get bigger.

Alas, almost all the seeds I planted either were eaten by insects or fried by my stupid decision to put a plastic dome over them during the day.

Miraculously, several seeds from the previous year sprouted in one of my raised beds, so I transferred them to solo cups and watched over them until they were strong enough to transplant into the larger containers.

They were slow to grow in May and early June, but by July shot up.

Soon they were my height, then taller, then towering over everything else in the garden at a height of 11 feet. I fertilized them regularly, and I think that and plenty of sun made them grow so big.

In August, flowers began to bloom and spill over in delicate droops of deep pink. So beautiful. And the stalks are like bamboo, very sturdy. The flowers lasted until I cut them all down in mid-October, though I realize now I should’ve let them stay on longer.

THE DISCOVERY OF PERSICARIA ORIENTALIS

Where does a plant “come from”? What is its “native distribution”? I defer to the experts because, to me, the question has an impossible answer. Where do you freeze time and say, “yes, this plant belongs here and doesn’t belong there”? In my opinion, any response is dependent on worldview/frame of knowledge. I’m a descendant of Europeans and speak European languages and have access to European resources, so my understanding is tied to that worldview.

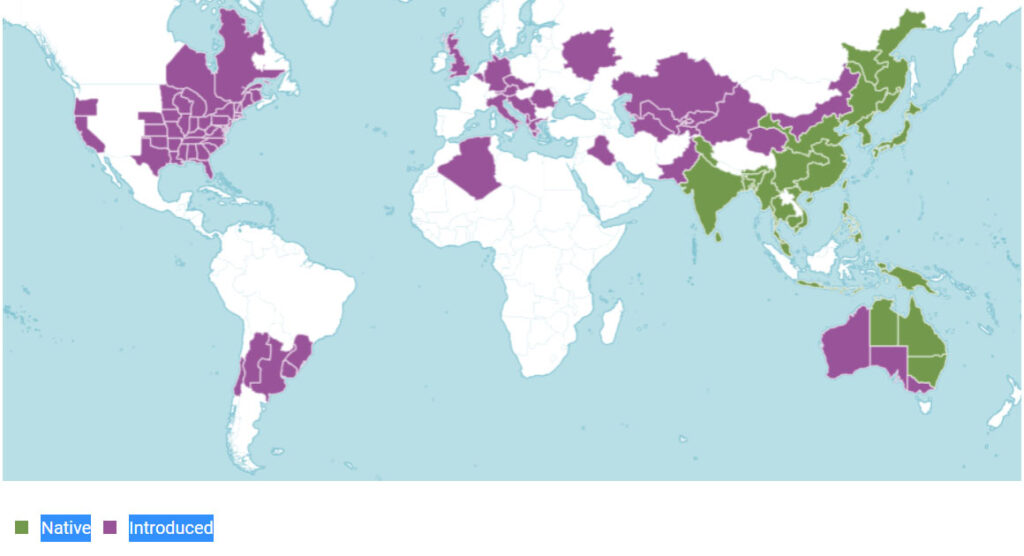

Here’s what that worldview says about Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate. Plants of the World Online, a joint program with The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, The Harvard University Herbaria, and The Australian National Herbarium, gives the species a large native distribution from India to Eastern Russia and Eastern Australia (see map below). Throughout my reading, the origin for Kiss-Me is often listed as China, India, or the Himalayas. At this time I haven’t found the reason for these published origins.

The first time the species is documented in European literature is in 1703 by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, a French botanist, writer, and academic who traveled extensively, collecting and documenting new species. In 1700 he left Paris and traveled through the Mediterranean and Black seas on an ambitious excursion. It was in modern-day Georgia that he and his travel companions first saw Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate:

We also went for a walk at the country house of the prince, which is in the neighborhood through which you arrive from Turkey. . . . It was in these gardens that we admired a beautiful species of persicaria with leaves like a tobacco plant, the figure and description of which I gave in an edition of L’Histoire de l’Academie Royale des Sciences. . . . Since the seed was not formed at the time, we beseeched an Italian Capuchin friar who had finished his mission in Tbilisi, and who would return through Smyrna, to collect some at the right time. This friar sent it, like us, to collectors in Holland and England.

Source: Relation d’un voyage du Levant fait par ordre du Roy, Tome 2, Page 316

After leaving Tbilisi, Tournefort traveled to modern-day Armenia where he again found the plants near the base of Mt. Ararat, the alleged location of Noah’s Ark:

The formal gardens which are on the left of the church are very nice. Amaranths and carnations make up their primary features, but these flowers are nothing special and do not merit us bringing seeds back to this country. In fact, the collectors of Persia would be much enhanced with species that we grow in Europe. In the monastery gardens, we collected only the seeds of that beautiful persicaria whose leaves are as big as tobacco, which we observed in Tbilisi in the prince’s garden.

Source: Relation d’un voyage du Levant fait par ordre du Roy, Tome 2, Page 338

Oh, Europeans. In one sentence self-aggrandizing, and in the next snatching an exciting new resource. Once the seeds were collected and sent back to Europe around 1702, collectors loved the tall, regal, and exotic looking flowers, which quickly spread through botanic gardens and large estates, where they were called Persicaria orientalis or Oriental Persicary.

So where did Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate come from? Beats me. It seems they were first seen by Western Europeans in Georgia and Armenia, but the English-speaking experts don’t even show them as an introduced species there on their maps. Go figure.

AMERICAN ARRIVAL OF ORIENTAL PERSICARY

The colonial influence of Europe at that time was wide, so it didn’t take long for Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate to hop regions again and find a new home in North America.

Among heirloom seed collectors there’s a story that Thomas Jefferson grew them in his famous gardens at Monticello, but this is debated. Peggy Cornett, the current curator of plants at Monticello and long-time historian of American botany, believes the story is false because of a confusion with early common names:

The plant Jefferson called “Prince’s feather” leads us down other paths of speculation. Because he compared it to the Cockscomb, we generally concur with Edwin M. Betts who, in his 1944 annotated edition of Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book, identified it as Amaranthus hybridus hypochondriacus. . . . During the late nineteenth century, however, another Asian species also called Prince’s Feather was Polygonum orientale, or Japanese Knotweed. Many names for this flower have persisted through time, including Princess’ Feather, Ragged Sailor, Kiss-me-over-the-garden-gate, Ladyfingers, Garden Persicary, Tall Persicary, and Oriental Persicary.

Source: “Naming the Flowers . . . According to Jefferson,” Monticello.org

Indeed it’s very difficult to trace the spread of this plant because there were so many different common names, the Latin-based scientific taxonomy was still being formalized, and many people were unable to distinguish between different species and varieties. There is strong evidence, however, that Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate was introduced to America by at least 1736. Again, Cornett is the most helpful:

Our earliest date documenting this Asian polygonum in America is 1736-37. That year Peter Collinson, a British patron of early American plant explorers, sent seeds to the Quaker botanist John Bartram of Philadelphia and to Williamsburg’s John Custis. In a letter to Bartram, Collinson wrote, “Inclosed, is some seed of a noble annual, — grows six or seven feet high, and makes a beautiful show with its long bunches of red flowers . . . . It is called the great oriental Persicaria.”

Source: “Naming the Flowers . . . According to Jefferson,” Monticello.org

Much like in Europe a couple decades earlier, the plant was then enthusiastically shared among collectors, planted in formal gardens, and introduced to seed catalogs across Eastern North America.

THE FALL OF PRINCE’S FEATHERS

The enthusiasm for Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate, however, did not last. By the end of the American Civil War, the species had evolved from an exotic and highly prized flower that collectors admired for its regal look to a weed that high-end gardeners associated with decay and neglect. The 1872 edition of American Agriculturist had this to say:

Some of the old-fashioned plants that were formally very common are now becoming quite rare. Some of these old plants we would not willingly spare, while we are glad to see the places of others occupied by more pleasing ones. Sun-flowers, Love-lies-bleeding, the large yellow Marigold, and the Prince’s Feather are in our minds associated with tumbled-down fences and neglected front-yards, and where these are the extent of the attempt at flower culture we expect to see the missing windowpanes supplied by an old hat or a bunch of rags. Those who do not thus associate the Princes Feather with poverty-stricken dwellings may find in it something of a certain coarse kind of beauty. . . Besides the name Prince’s Feather, it is also called “Ragged Sailor” and “Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate.”

Source: American Agriculturist. United States, Geo. A. Peters, 1872.

What. A. Snob. This is the first documented use of the name Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate (that I can find). In 136 years, it had lost its regal allure.

From this point on, people write about this plant in a bittersweet, nostalgic way. Poems reflect back on grandmother’s garden or on young love dashed by war and rough years.

I can only speculate as to why. By this time, the first industrial revolution had happened. People fled farms for the city and stopped learning how to grow and instead learned manufacturing skills. Many people died from fighting, disease, and enslavement during the Civil War, and in many places wealth, infrastructure, and agricultural knowledge were gone. The people who used to grow exotic varieties were dead, and those who still gardened most likely bought plant starts from nurseries instead of growing from seed, which is how Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate is best cultivated. It is also a self-seeding plant that doesn’t need much care, which means it can grow alongside weeds and other volunteer plants in abandoned places. But that’s just my take.

KISS-ME-OVER-THE-GARDEN-GATE IS BACK

What was old is new again, and over the last thirty years, Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate has made a comeback as the growing community of organic and heirloom gardeners rediscover the joys of old species.

This winter as part of the holiday card, I included a packet of Kiss Me seeds. I gave out 100 packets across the country and can’t wait to see how they do.

If you’re interested in growing this variety, try the following online seed shops:

Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

I’m super excited to get started planting my Kiss-Me-Over-the-Garden-Gate seeds.

We have frost now, so it looks like 1/4 inch under the dirt and wait till spring per week instructions. Looking forward to new growth!!!

I have one glorious plant towering over my garden! When and how do I gather the seeds please?

In early fall, you’ll see the flowers have almost finished blooming, and seeds start to form. At that time I’ll take a large ziploc bag (but you could use a large envelope or paper bag), gently dip flower/seeds clusters in the bag while they’re still attached to the stalks, and then flick or gently shake to dislodge the mature seeds into the bag. I do this a few times in the fall because the seeds don’t mature the exact same time. These become the seeds I share with friends and neighbors. Some seeds will obviously fall on their own, but that’s my favorite way of getting the new plants in my own garden the next spring. I watch for the seedlings in April/May, which I can recognize easily now, and transfer them to small cups for replanting later wherever I want.